William Tyndale's Bible

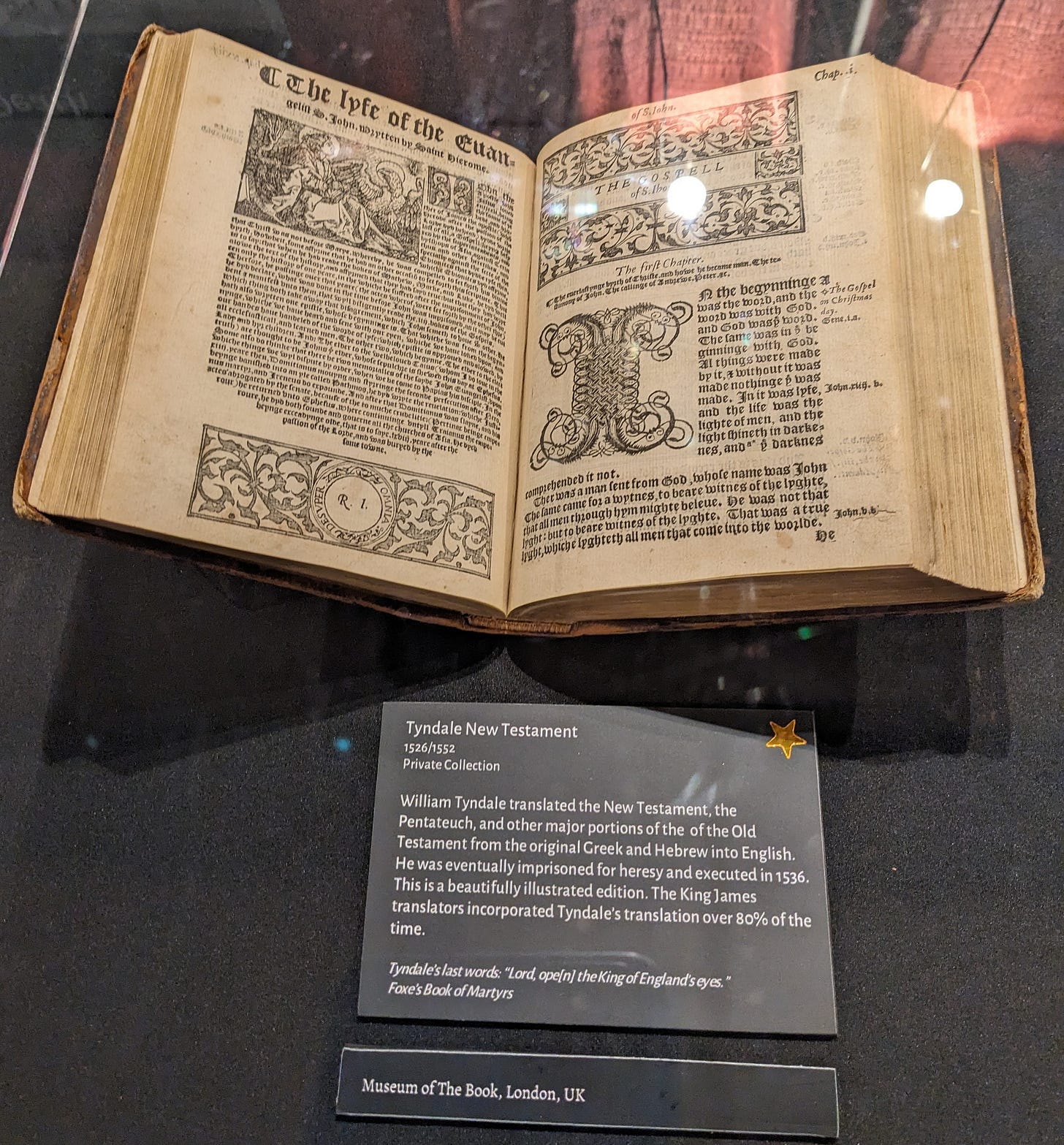

In April, our family visited the Inspired exhibit at the College of the Ozarks in Missouri. The exhibit featured the history of Biblical manuscripts and even included a Tyndale Bible, opened to John 1. I took a picture, and when I got home, I realized that it was the exact page Thomas Abell read in my fictional account of him living with the Protestant family.

As I have already written in other newsletters, William Tyndale was a contemporary of Thomas Abell. Although there is no documented relationship between the two, it is historically possible that they knew each other. They attended Oxford at the same time, and they both published a book denouncing King Henry VIII’s divorce, using the same printer in Antwerp.

I think that Thomas, as an Oxford-trained theologian with a passion for vernacular languages, would have had an opinion about William Tyndale’s work and the growing call for an English translation of the Bible. In my story, Thomas struggles with this concept, pulled between a love for tradition, a loyalty to the Catholic Church, and his love of scripture in all forms.

Who was William Tyndale?

William Tyndale is an Evangelical hero of the faith and a literary genius who shaped modern English as much as Shakespeare. His translation, completed in 1525, was the first English New Testament to be translated directly from the original Greek texts. His work served as the foundation for the King James Bible, published nearly a century later in 1611.

Because Tyndale’s unauthorized translations ran afoul of both English law and the Catholic Church's rules, Tyndale spent the last years of his life working in exile, primarily in Antwerp. He was eventually arrested in 1535, charged with heresy, and condemned.

When Tyndale was burned at the stake in 1536, his last words were, “Lord, open the King of England's eyes." Many Christian historians believe this prayer was answered three years later when King Henry VIII authorized the Great Bible, the first English Bible approved for public use in churches throughout England.

During the historical period that Thomas Abell served Queen Katherine of Aragon, Tyndale's work was making its way into the hands of the English people. Estimates suggest that as many as 3,000 to 6,000 copies were circulated in the initial publication run in 1526. However, English authorities, eager to squash the movement, bought and burned many of these copies. But instead of deterring the spread of Tyndale's translations, these efforts ironically financed further publications, as the money from the purchased books was used to print more.

When I was at the Inspired exhibit, I chatted with a docent about their Tyndale Bible, on loan from an English museum. He said that Tyndale translations were actually pretty common in London by the mid-1530s. Even though they were technically contraband, several well-known historical figures, including Thomas Cromwell and Anne Boleyn, held copies. And it would not be an exaggeration to suggest that Thomas Abell may have had access to a Tyndale Bible as well.

Thomas Abell, after writing Invicta Veritas in 1532, spent a few months hiding, avoiding the king’s wrath. We do not know where he disappeared during that time, but I have placed him in London, hiding under the king’s nose in the house of a protestant merchant, a Tyndale supporter.

Here is part of a scene from that chapter.

Thomas Towers

The first night Thomas joined Danielson’s family, he edged to the back of the sitting room as the family gathered around the hearth. Danielson’s wife Susanna reached behind the egg basket, pulled away the stock of drying onions, and found the rag bundle that concealed the Tyndale New Testament. She gingerly handed it to her husband.

The humbly bound book was so different from the chained vellum versions of the Vulgate Thomas cherished. This one, though larger than a prayer book, could be held in one hand. The leather binding, though new, was already worn.

Would there be a day when every English household would have a hand-sized Bible? Would every family have someone who could read it aloud? What about the parts that were difficult to understand? Would there be priests and doctors of the Church, trained experts, to explain these things to them? Would people simply take it for granted when it became common?

For Thomas, going to the library to read the Word of God in Latin had been a holy treat, an activity saved for special days, a reward for years of Latin study. If the Bible was available for anyone at any time, would they forget that it was Holy?

Danielson carefully opened the book to the page he had read the night before and began reading, Matthew, the teachings of Jesus, the story of the Sower. It was both foreign and familiar to hear the parable in English. Thomas leaned in. What English words had William chosen for the passage he knew in Latin?

The youngest of Danielson’s children fidgeted, wiggling in his mother’s lap, but the other five children sat quiet, eyes focused on their father. One of the girls, seated at her mother’s feet, twisted the blond hair that fell disheveled outside her sleeping cap. Her younger brother sat rigidly on a three-legged stool. He sucked his fingers while he listened. A farmer went out to sow a crop.

Thomas, of course, knew the story and had read it to his Oxford parish in Latin, but to see the children’s faces, hearing the story for the first time, somehow dramatized it in a way he had never heard it before. A farmer went out to sow a crop. These children, this next generation of Englishmen, were soil right before him. This was Tyndale’s dream, children hearing God’s word in their native language. Tears sprung to his eyes. William, I wish you could hear this.

If only the Bible could be legally printed in England like it was in France and other Catholic European countries, which allowed the vernacular scripture. There had been no official papal edicts forbidding the Bible in English. That prohibition had been the work of Parliament after the Lollard uprising. There was no reason there could not be an official translation sanctioned by both the king and Pope. Surely, it would benefit all.

Thomas closed his eyes and prayed it would be so.

When Thomas opened his eyes, he saw Danielson watching him. The children turned their gaze to Thomas. He smiled. “Do you want to read the scripture?”

It did not sound like a challenge, but Thomas hesitated. The Bible was still contraband, officially illegal. Possessing a copy of the book was enough to warrant arrest. And yet, he had written a book like that, too.

He opened his palms. Why not?

“Thank you,” he said, taking the leather-bound book in his hands. This was the project William had labored for. He gently turned the delicate pages to the first chapter of John. He knew that part by heart in the Vulgate. Like an Italian tune or an English melody, the Vulgate’s Latin version of John 1 resonated like music as it flowed out of his mouth.

“In principio erat Verbum et Verbum erat apud Deum et Deus erat Verbum,” he breathed out with a sad smile. He had not been much older than Danielson’s boys when he learned those beautiful lines. He smiled at the children’s faces and then looked at the page in his hand, “In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God: and the Word was God.” He smiled. Well done, William. It was a perfect translation.